Stream & Dance: Contempo Arts' Fused - Part II

Streaming a live event is not the same as being in the theatre, but that doesn’t mean the stream has to be less than being in the room. Contempo Arts’ Fused shows one way live events can be streamed effectively.

Fused has extended its run! It’s still streaming here through 10/26 2022. Tickets start at $11.25.

As I mentioned in part I, I was at a board game shop. This is the last place you’d expect to find a flier for the fine arts, but Geeky Teas displayed it prominently near the counter.

Check the place out yourself if you’re in the area! We need more small businesses that support local artists! Vote with your feet; vote with your wallet.

Being There vs. Watching from Home

There are a number of differences that are so obvious and glaring that we completely overlook them as performing artists. However, most can be seen if we just consider our audience’s perspective, where they are, what’s around them.

Live: There is a massive apparatus that focuses the audience’s attention. It’s what we perform in, and it’s so ubiquitous to us, we forget it’s there or what it does. It is the theatre itself.

Streaming: Our audience could be anywhere at all. It could be 6pm on a Saturday in their living room, noon Sunday in the kitchen with kids screaming for ice cream waffles, 2am in bed sleepless on a Tuesday, in an airport, in the dentists’ office waiting room, anywhere at all. And without the giant apparatus and social reinforcement of a theatre filled with other watchers to help our audience focus.

But it’s not impossible to make a compelling stream from a live performance. In fact, TV has been working on this exact same problem for close to a century, and has developed techniques to make a great experience for remote viewers. All we need to do is borrow those and adapt them for ourselves.

Props to Adam Bloodgood

Adam Bloodgood is both a videographer and a ballet performer. In fact, he had the lead role in Contempo Arts’ last production.

What’s extraordinary about Adam Bloodgood is that he not only took the stage in Romeo and Juliet, but also gave the stage as the Videographer for Fused.

Since the performance doesn’t differ between nights, Mr. Bloodgood could take one or two cameras and place them at new angles to make it appear there were three or four cameras in use. Since he was using cameras with 4K sensors, he allowed the editor, Yuan Elizabeth Yang, to push in on shots without losing picture quality. That makes it feel like even more cameras were in use.

All in all, you don’t need a vast fleet of cameras for your live performance to make it feel like its covered like a rock concert. Two can be enough for scripted and choreographed performances. Mr. Bloodgood makes economic use of his equipment.

I’m highlighting his work in particular to show that a performer can (and perhaps should) be technical. We do not need to rely on others for the success of the arts. We can effectively, and artistically operate cameras, switchers, and every instrument needed for streaming our work.

Because Mr. Bloodgood is himself an accomplished Ballet performer, he was able to make good videographic choices to illuminate the work of his fellow dancers.

One thing Twitch, Youtube, and the Pandemic have taught us is that we’re all capable of operating our own equipment, and developing our own apartment-streaming-studios.

Mr. Bloodgood demonstrates that these skills don’t need to be thrown away as we come back together on the same stage. We can operate the cameras ourselves for the other performers and continue innovating a fused digital/analogue theatrical renaissance.

Videography

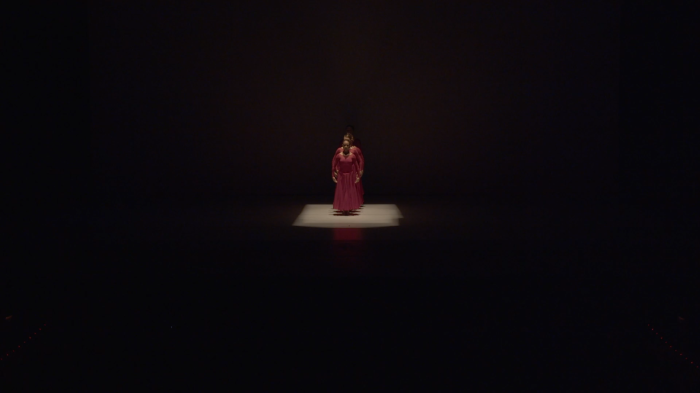

One obvious difference between live and streaming performance is the picture.

This isn’t exactly a fair comparison. For one thing my phone sweetens the colors more than the streaming video. For another, I’m using a wide angle on my camera phone, which will make the players look even smaller on the stage. But it still highlights some of the tradeoffs.

Live: My viewing angle is limited, but I get the full range of my eyes and head. I can rove around the stage as I please focusing where I like. I also get an authentic non-digitized, uncompressed visual using the full range of colors that my eyes can perceive. I can also feel the energy of the performers’ physical presence, and the same goes for the audience around me who I can sense sharing my experience.

Streaming: My view is greatly expanded. It’s limited only by the number of camera angles the videographer has chosen. But what I view at any given time is chosen by the editor and the videographer. I have some freedom to look around the 16x9 picture frame, but not nearly as much freedom as seeing the performance live.

The picture is digitally compressed and not as vibrant as being in person. I also don’t get the sense of presence from the performers and the audience around me. That energy is not captured by the camera sensor.

Also, the rest of my environment, whether I’m in my home or out on errands, is competing for my attention and I’m much more easily distracted. And if it’s recorded, knowing I can pause the performance and come back also lessens my commitment to it.

The key thing to remember here is that videography and editing become as important to the performance as what’s being done on stage. The audience is relying on you to point their eyes for them. If you get that wrong in videography or in editing, the audience will rebel and find reasons to look away. If you get it right, they’ll be glued to the screen regardless of what’s happening around them.

You can’t just point a camera at the stage hit record and expect that to be good enough. Otherwise 100 years of film history would be locked-down single cameras at the back or side of the house.

Sound

Sound is a squirrely problem for videographers, but it has an easy answer for streaming dance. Don’t record sound.

Instead just sync the video to the music tracks that were used in the live performance.

Benefits to this approach:

- No need to get the right microphones or work out where to put them.

- No need to worry about mixing the live sound into the recorded music so that you don’t get weird distortions.

- The music is already mixed by the recording artists who created it.

Drawbacks:

- It’s not as lively.

- You don’t get to hear the dancer’s feet, or the live audience’s reactions.

- Lack of rich audio separates you from the performance.

Editing

Yuan Elizabeth Yang does an excellent job editing the shots, cutting on moments when the audience will want to blink or see a new perspective, and cutting to the rhythm of the music.

To the discriminating eye looking specifically to the editing without being “distracted” by the performance, there are times when the picture is not balanced between cameras.

Not balanced means that there are differences in the picture quality taken by the two cameras which make it appear to be two different performances. One camera records the performance bright and blue. The other is darker and more yellow in comparison. These images can be balanced with color correction in a program like Davinci Resolve.

Most likely, the reason that wasn’t done is because attempting to correct the picture had even more distracting effects. I’ve personally had situations like that attempting to balance a camera phone with a digital cinema camera. Sometimes you simply have to accept the imperfection and hope the performance is strong enough to push through it.

Like the live performance itself, the process of videography and editing is just as much a practice of working with and accepting imperfections. Yuan Elizabeth Yang makes good and sensible tradeoffs.

What Fused can Teach us about Art

Is it the same thing? Seeing the performance live versus streaming it? Well, no. The experience is different.

Is it even the same art form? Perhaps yes, perhaps no.

In one sense, the addition of the Editor and the Videographer changes things. They make specific aesthetic choices when presenting the work. That means they have a hand in crafting the sreaming performance where their infuence is not felt in the live performance. Perhaps no?

Also the audience is not in the same room. That changes their experience. So perhaps no, it’s no longer the same art form.

But the performers still present their art the same. The addition of digital streaming equipment is gently molded to the performance after the fact. Long ago, theatre happened outdoors in the daytime when the sun could light the stage. It wasn’t called something new when 16th century courts moved the theatre indoors and used candlelight. So perhaps yes, it is still the same artform.

Nevertheless, as more performers like Adam Bloodgood cross the sightline of the camera lens, more and more experiments will be conducted. More performers will become familiar with the instruments of streaming, and the technology will begin to influence their performances. “You make the tool; then the tool makes you.”

So is it even the same art form? Perhaps yes, perhaps no. This might be like asking “Is Ballet Fusion still Ballet?” And maybe it’s best to not even make that categorization. Our categorizations limit us. Art should have no limits.

Heisenberg says when we observe something, we change it. If that’s true, perhaps this digital fusion has already begun. Adam Bloodgood’s example, and Contempo Arts’ production of Fused may be the first of many new streaming performances.

Fused has extended its run! It’s still streaming here through 10/26 2022. Tickets start at $11.25.