This Grief Will Be of Use

Perhaps the most diabolical way slavery influences us today is how it’s still taboo to address it. Constance Strickland and Theatre Roscius touch the taboo to spin a new history of healing.

A History of Grief that still lives today

The heat is oppressive this Saturday as I walk/run through the Arts District. Just getting to the installation in time has a sympathetic vibration with what I am about to experience. Even this neighborhood was purchased from the poor to sell to the wealthy. The auction block reverberates today in a thousand subtle ways.

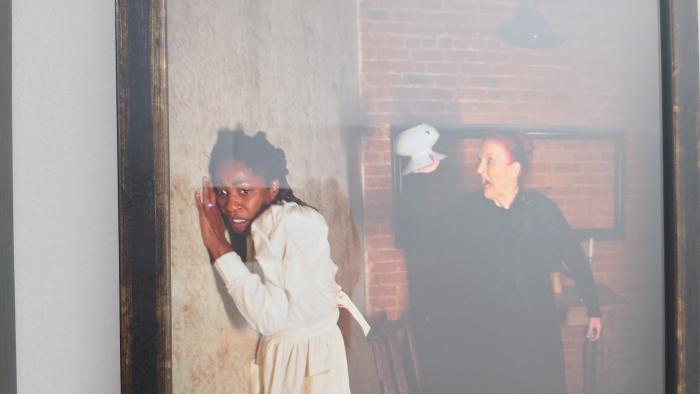

Rushing into Art Share LA, navigating several weaving turns, I find myself at the event. Raw cotton is everywhere. I have only just sat down. I’m still fumbling with my useless wide-brimmed hat when a spectacled White Woman in Victorian clothing asks me “Am I too late? Oh it’s just starting. Good.”

Turning forward, I see a Black Woman.

She faces away from me, shoulders hunched, clasping something unseen about the size of a baby to her chest. She’s in rags standing on a tree stump next to boiler piping in unforgiving overhead fluorescent light. She is slick with sweat. The air is hazy in the brick-confined quarters. I am just in time for a slave auction.

It was only fifteen minutes, but a whole history of force, intimacy, dependency, and grief perpetrated by women on fellow women was contained in it. Through the art installation I felt more than saw a painful, but important aspect of my own family’s history that has been painted over — white-washed in every sense of the word.

“This was years of research.”

Constance Strickland told me between performances.

Her next showing was in five minutes.

Ms. Strickland studied the works of historians Elizabeth Fox-Genovese and Stephanie Jones-Roger on the simultaneously intimate and destructive relationship between white women protecting their economic freedom through investments in slave ownership, and the black slaves they came to depend on for leverage in a patricarchal society.

“Growing up in Arizona in a white environment as the only black girl, this may have always been made/led me here to this work. The fact that White womanhood did not see Black women prolonged so much progress. The white patriarchy fed off the broken relationship between the two races of women.”

Going beyond the objective research of the book, Ms. Strickland has created This Grief Will Be of Use, physical theatre and art installations that educate what our lost history felt like. This one being Part II. Part I was a 30 minute physical theatre piece.

“I hate to put things into academia, but it’s a new way of teaching history. This work though is educational work - a way of showing history without it being told in a book, talked at to students.”

From the audience, this was less like watching a historical film where the screen still separates you from the action, and more like feeling everything resonate somewhere deep in your mitochondrial DNA. As a white male of southern descent, it has been a powerful and healing experience. My family, like many southern ones, has trouble confronting itself.

Visceral artwork takes visceral tools

Work like this is exceptionally challenging – both physically and psychologically dangerous. It takes committed training in specific theatrical techniques along with bail-fulls of trust with your fellow players to approach such deep and personal pains.

“I can’t approach this work without Mary Overlie’s Viewpoints, Anne Bogart’s Viewpoints and Tadashi Suzuki’s training”

In Ms. Strickland’s hands, tools used for actor training become wrecking balls and crowbars tearing apart the structures that silently oppress us from the backs of our minds. Stanislavski’s “Method” doesn’t have the expressional power to turn the pain of 200 years into 15 minutes. But with these novel techniques, Ms. Strickland demonstrates that there are oceans of possibility for any new play or narrative improv show to have a serious impact.

The physicality alone is not enough though. Ms. Strickland has created deep trusting relationships with her fellow performer Michelle Holmes and her Director Breigh-Ann who also plays a world-building role in the Performance Art. This trust allows for the past the installation presents to affect the future.

Michelle Holmes performs a monologue, improvised freshly each performance in her own words where her character comes to the realization that all of this pain and abuse – “It’s my fault.” She comes to those words on her own, and Ms. Strickland specifically did not write the monologue because “I’m not white. I can’t tell you what you will say.”

But this history can be of use

But why even go there? It was terrible. It’s in the past. Why dredge up old wounds and make ourselves uncomfortable? Why not just move forward?

“These slave men and women and babies were stolen from their homeland. They lived whole and vibrant lives in Africa. That memory our tongue, our language was stolen and the work is a way to remember and rework the past and to honor the Black women who were in forced bondage.” Constance Strickland

The past stays with us even if we forget it or rewrite it. It influences us in a thousand tiny ways that seem random and inexplicable, yet they point back to real events. Both the terrible and the noble. Blessing or curse, it is entropy, a law of physics, that no information is ever fully lost, erased, or whiped clean.

And the oppressors are damaged as well. For every action has an equal and oposite reaction. Unexamined, we repeat the violence echoing the very actions we hope to ignore. The grief can’t be forgotten.

To heal, we must accept it all.

There’s an old improv adage, “The only way out is through”. And in massage therapy, Mongolian Skeletal Cleansing deeply touches where a blow landed on the body to free the spirit from the memories of violence. By explicitly reconstructing the traumas of our heritage, we can give voice to our grief and heal the damage.

This is why in the performance, The White Woman comes back as a ghost to deliver her monologue of realization. It’s a thing that is obviously impossible from a historical perspective, yet exactly what’s needed to reset a history of trauma that is deep in our bones.

It’s also why the performance ends with a listing of names black ancestors gave themselves in secret, even as their white oppressors called them something else. Both the monologue and the names take back control and allow the audience to own the past so they can chart a new future with it.

It is a poetic irony that our trauma is the very fuel we can use to set ourselves free.

The grief is of use.

What the future holds

This Grief Will Be of Use Part II ended its run last weekend, but the future holds more for Theatre Roscius.

“There may be a Part III per se, but I will be exploring the relationship between Black women-colorism and the effects of slavery within that relationship.”

“If anything I’m looking to take this into VR where people can choose their own adventure. You can be the plantation owner or the slave, or the human bondage person.”

You can find out more and support Theatre Roscius here.