Your Zoom Show has a Speed Limit

![A radar communications dome tracks polar orbit satellites in the arctic [photo credit: Steve Hogan]](/blog/your-zoom-show-has-a-speed-limit/headline_hu76a8af89271fbf16833937d00df29785_125364_1280x400_fill_q75_box_smart1.jpg)

Performing over Zoom is not like performing in person. In many ways, this is a good thing. With Zoom, people can perform remotely from all over the world. But there are limits. One in particular is pretty sneaky. Physics.

In Star Trek, humanity has broken the light barrier. That is, we can travel (and communicate) effectively faster than the speed of light. Some are trying to achieve that vision right now, but with limited public success.

When we figure out a way to communicate faster than the speed of light, this article will be moot, but don’t expect that to happen soon.

Why mention the speed of light? I thought we were talking about Zoom shows.

The answer is Latency.

Latency and Relationship

![A mare and her foal don’t experience latency when they touch muzzles. [photo credit: Steve Hogan]](/blog/your-zoom-show-has-a-speed-limit/images/MareAndFoal_hu1d1872cfc246f317d9508f60ad100e69_4198872_700x0_resize_q75_box.jpg)

Try an experiment with your favorite Zoom show. Play it back at 1.5 speed. I guarantee it’s funnier and richer. Why does this work? Because you’re compressing the latency between the performers.

Latency means “lag”, or “delay”. It’s the time it takes for a signal to go from one place to another. For instance, when I mailed a letter from Los Angeles to Baltimore in 2008, the letter’s latency was around 2 weeks. Phone call latencies are much faster. Being in the same room with someone is so fast the human body perceives it as instant, but it’s not.

The speed of sound on Earth at Sea Level with an air temperature of 15 degrees Celsius is 761.2 mph (340.27 meters per second). That means that when you speak to someone about three feet away (1 meter), their eardrums will vibrate 2.9 milliseconds after you have spoken. Light is much faster than this, of course.

Audio engineers use 3 milliseconds as the gold standard for the perception of “no delay” when a performer listens back to their own recording. [SBE Broadcast Engineering Handbook sec 5.2.7 Delay]

5 milliseconds is an acceptable upper-bound. After 5 milliseconds, users will start to complain they’re hearing a “slap” or a distracting level of feedback from the delay.

So, with 3 milliseconds’ delay, a listener will perceive the same closeness as being within three feet of the speaker. (That is, as if they could reach out and touch).

Closeness without delay is essential to improv,

or any ensemble that performs arts

where relationship matters.

Delay makes you feel isolated, disconnected. This is one of the greatest limiters of Zoom shows. The improvisers, the actors, feel like they’re on a call, not having a relationship.

As human beings, what we want to feel most from small team arts like improv is that relational closeness. It’s more important than jokes, gags, or bits. It gives all of those comedy moments added emphasis and meaning.

But why didn’t all this matter in TV production?

Because the performers didn’t feel any latency. They were all on the same set together. The audience might see them minutes later, but all their reactions were based on what the performers could feel from each other, quick-as-lightning. That lightning can never be so quick on Zoom.

The Speed of Light

![A humming bird can flap its wings once in 19 milliseconds.<br>

Light can travel 3,509 miles in that timespan.<br>

[photo credit: Steve Hogan]](/blog/your-zoom-show-has-a-speed-limit/images/hummingbird_flight_hub01a0e39d986acc899c89a6e315998aa_1516622_700x0_resize_q75_box.jpg)

Light can travel 3,509 miles in that timespan.

[photo credit: Steve Hogan]

Much as sound has a speed, light has one too. The speed of light is labeled c in e=mc2 because Albert Einstein showed through mathematics and experimentation that c was a constant of our universe. The Constant. It is ~670 million mph (299,792,458 meters per second)

What Einstein says, and what GPS satellites do proves, that as you go faster, time slows down. That doesn’t mean much walking or driving a car, but it matters in orbit.

If you were to go at the speed of light, you would see time stop for the world around you.

Theoretically, if you were to go faster still, you’d see time move backwards and you’d arrive at your destination before you left. No one has ever done this, and no evidence in 100 years of measurements has ever shown anything, not even tiny particles, breaking this speed limit.

Maybe you could do it by folding space like they do in Star Trek, or like a black hole does beyond its event horizon, or at the edge of our expanding universe where galaxies are pushed away from us at ever-increasing speeds.

We can assume for now that no warp drives, black holes, or distant galaxies are involved in the delivery of our video feed.

But so what? The speed of light is still really really fast.

Fast as it is, it has limitations on what is possible over Zoom.

Zoom and the Laws of Physics

![A Pennsylvania road extends past farmlands<br>

to old mountains in the distance<br>

[photo credit: Steve Hogan]](/blog/your-zoom-show-has-a-speed-limit/images/PennsylvaniaRoad_hu8e874c2f42ddd6c19648626b94ee27e3_4749460_700x0_resize_q75_box.jpg)

to old mountains in the distance

[photo credit: Steve Hogan]

The circumference of the Earth, ignoring all those mountains and valleys for a bit, is about 24,000 miles. Which means (until we discover how to send signals directly through the earth’s crust) the farthest any two Zoom improvisers are on the planet is ~12,000 miles (20,037,137.5 meters). Light can traverse that distance in 67 milliseconds. That’s pretty quick! Blinking your eyes takes between 100 and 400 milliseconds.

But it’s still ten-times longer than 5 milliseconds, which, as audio engineers discovered, is how long the delay can be before it’s noticeable by human beings.

This means that doing Zoom shows with anyone on a different continent than yours will have inherent limitations. No matter how hard you try, it will not feel as connected for you.

If the audience plays back your recording at 1.5 speed, or someone trims those latencies out of the show by editing it in post, it will feel great for the audience, but not for you. That’s the cost of distributed performances. The further you are apart, the greater the latency, the less the connection.

Fast-banter comedy bits won’t work, timing will be off,

and relationship will be muted.

Musicians in lock-down discovered this problem almost instantly. Music absolutely requires precise timing. Improv is more plastic, more adaptable. It was able to carry on, but at a price.

Even if technology improves, and you have a computer so fast it can encode the camera’s feed and send a 1080p video instantly, AND the internet’s network connections send the signal instantly as well, the farthest someone can be from you is 931.4 miles and still feel like they’re right there with you. It’s a big hop larger than three feet, but it’s not the whole planet.

In LA, that limits me to anyone as far away as Oregon, most of Colorado, Baja, Northwestern Mexico, and a huge wasteful swath of the Pacific Ocean where nobody lives.

Seattle is 34 miles too far. Maybe I can convince some of my friends in Washington to go in on a houseboat…

Get a little Closer

![“Toads in Love”<br>

Two toads get close together on an old log in a marsh<br>

[photo credit: Steve Hogan]](/blog/your-zoom-show-has-a-speed-limit/images/ToadsInLove_hu1d1872cfc246f317d9508f60ad100e69_479022_700x0_resize_q75_box.jpg)

Two toads get close together on an old log in a marsh

[photo credit: Steve Hogan]

Zoom, our computers, and the internet itself add even more to the latency. They use time to encode, transmit, transcode, route, and decode the video.

There is already hope technology will improve. But regardless of software optimizations, no matter how much gear we buy, or what new technologies we employ: Virtual Reality, Motion Capture, Machine Learning, Computer Vision, none of these can do anything about the speed of light.

To limit latency, to increase that sense of relationship and intimacy that so many of us crave, nothing beats being closer. Lessen the distance. Lessen the network hops. Be in the same town, or even the same studio, covid willing. Otherwise, physics. You will just feel the connection less while you create.

Then again, if you know about latency, there may be ways to improve remote distributed art. Maybe post your Zoom shows at 1.5 speed to begin with. Maybe pre-record just before, then have the cast watch along and feel the connection along with the audience. Who knows what adaptations we can employ to bring back that lovin’ feeling.

Now that you know those limits, you can play to Zoom’s strengths better.

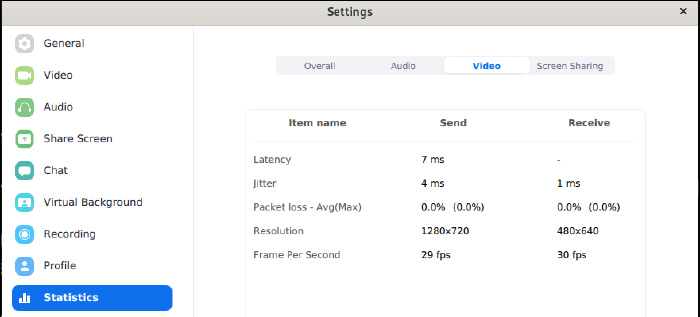

will sometimes dip below 5 milliseconds.

Test it out with your whole team to see where you stand.